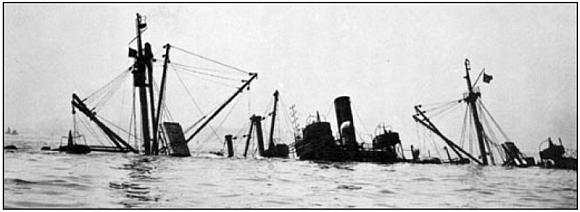

El Estero scuttled Near Robbins Reef, New York Harbor

Bowsprite was kind enough to pass along this forgotten moment in history, which fits in well with recent posts. Like the case of the Liberty ship SS Richard Montgomery, it involves a ship loaded with high explosives and like the apparent “Blind Date” hoax, it is about an explosion, which did not happen, though unlike the Blind Date hoax, it came perilously close to being a major disaster. The fire in New York harbor of 1943 has been rightly called the greatest nautical disaster that didn’t happen.

On April 24, 1943, the day before Easter, around 5:30 PM, a fire broke out in the engine room on the SS El Estero. The ship had just finished loading ammunition at the Caven Point docks, between Bayonne and Jersey City, NJ, just across the harbor from lower Manhattan and Brooklyn. In addition to the ammunition and explosives in the holds and stacked on the deck of the El Estero, two other ships were also loading ammunition in the terminal from rail cars. In total 5,000 tons of high explosives were on the ships or on the dock. There were also large fuel oil tank farms near by in Bayonne and Staten Island. If the munitions were detonated by the fire, the explosion could have had the force of a tactical nuclear weapon, potentially leveling everything in a five mile radius. The blast area would have included much of lower Manhattan, Brooklyn and Staten Island and all of Jersey City, Bayonne and parts of Newark.

The fire in the El Estero’s engine room was started by a flashback from a boiler which ignited oily bilge water. Five fire trucks from the Jersey City Fire Department and two 30-foot fireboats from the U.S. Coast Guard arrived by 5:35 pm, followed by about 60 volunteers from the Jersey City Coast Guard station. By 6:30 pm, New York City’s much larger fireboats John J. Harvey and Fire Fighter arrived and ran hoses to Coast Guardsmen on the deck of the burning ship. Coast Guard Lt. Commanders John Stanley and Arthur Pfister took command. Lt. Commander Pfister, a retired battalion fire chief in New York City and officer-in- charge of Coast Guard fireboats, assumed overall responsibility for firefighting while Lt. Commander Stanley directed activities on the El Estero.

Despite large streams of water pumped into the ship from the fire trucks and the fireboats, the engine room oil fire was burning out of control. The boats and trucks also sprayed water on the ammunition stacked on deck and in the holds of the ship in an attempt to keep it cool. Four tug boats were summoned to haul the burning ship away from the dock. Lt. Commander Stanley asked for twenty volunteers to stay on board with him and Pfister to fight the fire during the transit. By 7:00 p.m., the seamen on board El Estero secured a steel hawser to the ship’s bow and the tugboats began pulling the burning ship out into New York Harbor.

The tugs towed the El Estero to a more isolated location near Robbins Reef Light in Upper New York harbor, where the fireboats Fire Fighter and John J. Harvey continued to to pour water into her until she settled to the bottom, shortly after 9 pm. By 11:30 pm, all fires were extinguished and the fireboats returned to their docks. Remarkably, no was killed by the fire.

News coverage of the disaster that didn’t happen was limited. It was war-time and there were enough news accounts of ammunition ships that did explode to fill the pages of the newspapers.

In December 1944, the four tugboat captains who pulled the burning ship to a safer anchorage; Ole Erickson, Gustaf E. Carlson, Anthony Striffolino, and John Gully; were awarded the first Merchant Marne Meritorious Service Medal. John T. Stanley was awarded the Legion of Merit for his role in fighting the fire and Arthur Pfister was awarded the Navy and Marine Corps medal.

Recognition of the heroism demonstrated by the enlisted personnel in fighting the fire was slower in coming. The enlisted men were honored by the city of Bayonne with a parade and citations, but received no medals from the Coast Guard at the time. Seymour Wittek, who was a 22 year old Seaman Second Class in 1943, petitioned the Coast Guard and New York City for recognition of the enlisted personnel in fighting who fought the El Estero fire. Finally on Veterans Day in 2008 at the Intrepid Sea, Air and Space Museum in Manhattan, Vice Adm. Robert J. Papp Jr. presented Mr. Wittek with the Coast Guard Commendation Medal for bravery. The Coast Guard later presented the commendation to at least two other members of Mr. Wittek’s unit, one posthumously. Seymour Wittek died in 2010 at the age of 88.

Seymour Wittek Dies at 88; World War II Hero at Home

That was a great story. Anyone ever write a book about it?

My Father was one of the tugboat Captains who helped tow and scuttle it.

My Father was one of the tugboat Captains who helped tow and scuttle it.

The proof was written on 10/30/44 in the Bayonne Times. I have the original copy of it along with his picture.

I have written a book on Ships to remember being published by History Press in England. My new book is on Tugs to remember and I have written the story of the SS El Estero. I desperately need to know so much more about the 4 tug boats….names images etc…I have 7 tug boats painted so far including the Texas city disaster. I have the skippers names of the 4 tugs.

Much appreciated to receive an email….

Austin Dwyer ASMA

My father was on duty with the coast guard during that fire. Does anyone know if they were ever recognized for their bravery?