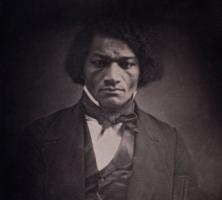

Frederick Douglas

Frederick Douglass never knew his birthday but he chose to celebrate it every year on February 14th. So happy Frederick Douglass’ birthday and a most joyous Valentine’s Day.

Frederick Douglass was born a slave around 1818. He taught himself to read and write and at 20 years of age, escaped to freedom. He would become known worldwide as a gifted orator, author and editor and as a leader of the abolitionist movement. He was a severe critic of President Lincoln and also a close adviser. He would help recruit black soldiers to fight for the Union in the Civil War and, after the war, would fight against Jim Crow laws in the South and for women’s suffrage and immigrant’s rights. Frederick Douglass is an American hero, of his time and of ours.

From an early age, Douglass developed a close attachment to ships and the sea. His path to freedom led directly through the docks and shipyards of Baltimore, Maryland. He was sent to work in the shipyards at Fells Point as a caulker and shipwright’s helper when he was around 12 years old. In the shipyard, he learned the first letters of the alphabet — “L” and “S” for larboard and starboard and “F” and “A” for fore and aft, from marks made by the shipwrights on ship’s frames to identify where they were to be placed on a ship under construction.

As a slave his proximity to ships and the bay was both a torment and an inspiration. He would write in his biography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass:

Our house stood within a few rods of the Chesapeake Bay, whose broad bosom was ever white with sails from every quarter of the habitable globe. Those beautiful vessels, robed in purest white, so delightful to the eye of freemen, were to me so many shrouded ghosts, to terrify and torment me with thoughts of my wretched condition. I have often, in the deep stillness of a summer’s Sabbath, stood all alone upon the lofty banks of that noble bay, and traced, with saddened heart and tearful eye, the countless number of sails moving off to the mighty ocean. The sight of these always affected me powerfully. My thoughts would compel utterance; and there, with no audience but the Almighty, I would pour out my soul’s complaint, in my rude way, with an apostrophe to the moving multitude of ships:– “You are loosed from your moorings, and are free; I am fast in my chains, and am a slave!”

...Why am I a slave ? I will run away. I will not stand it. Get caught or get clear, I’ll try it. I may as well die with ague as with fever. I have only one life to lose. I may as well be killed running as die standing. Only think of it : one hundred miles north, and I am free ! Try it ? Yes ! God helping me, I will. It cannot be that I shall live and die a slave. I will take to the water…

When Douglas finally did escape to the north, he did so disguised as a sailor. In his biography, he describes his outfit:

“In my clothing, I was rigged out in sailor style. I had on a red shirt and a tarpaulin hat and black cravat, tied in sailor fashion, carelessly and loosely about my neck. My knowledge of ships and sailor’s talk came much to my assistance, for I knew a ship from stem to stern, and from keelson to cross-trees, and could talk sailor like an “old salt.”

Douglas boarded a northbound train. He had no “free papers” showing that he was not a slave, but had borrowed a “sailor’s protection” from a free black sailor. The protection allowed free black sailors to travel between ports. He wrote:

On sped the train, and I was well on the way to Havre de Grace before the conductor came into the negro car to collect tickets and examine the papers of his black passengers. This was a critical moment in the drama. … Seeing that I did not readily produce my free papers, as the other coloured persons in the car had done, he said to me, in a friendly contrast with that observed towards the others : ” I suppose you have your free papers ? ” To which I answered : ” No, sir ; I never carry my free papers to sea with me.” ” But you have something to show that you are a free man, have you not?” “Yes, sir,” I answered ; ” I have a paper with the American eagle on it, and that will carry me round the world.” With this I drew from my deep sailor’s pocket my seaman’s protection, as before described. The merest glance at the paper satisfied him, and he took my fare and went on about his business.

Douglass counted himself fortunate that the conductor did not look closely at the sailor’s protection as it described a very different looking individual from himself. From the train, he traveled by ferry, another train and by steamer to Philadelphia and New York. In New York, he married Anna Murray, a free black woman that he had known in Baltimore.

They moved to New Bedford, Massachusetts in 1839. The Quaker whaling port was a hot-bed of the abolitionist movement. Douglass would give his first abolitionist speech at the Massachusetts Anti-Slavery Society’s annual convention on the island of Nantucket in 1841. It would be the first of thousands of speeches and editorials that he would give or write condemning the institution of slavery.

He wrote his first autobiography in 1845, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, which was a best seller. Within three years, the biography had been reprinted nine times, with 11,000 copies circulating in the United States. It was also translated into French and Dutch and published in Europe. Money from the book as well as help from supporters in England provided Douglass with the means to legally buy his freedom in 1846.

In 1855, Douglass published My Bondage and My Freedom. In 1881, Douglass published Life and Times of Frederick Douglass, which he revised in 1892.

While one uninformed individual and his press secretary recently implied that Frederick Douglas is still alive, Douglas did, in fact, die of a massive heart attack on February 20, 1895.

Pingback: Escape by sea | Rturpin's Blog