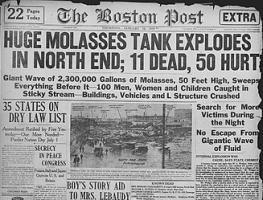

Today marks the 100th year anniversary of the Great Boston Molasses Flood, which inundated Boston’s North End sending a wall of molasses, killing 21 and injuring 150.

Today marks the 100th year anniversary of the Great Boston Molasses Flood, which inundated Boston’s North End sending a wall of molasses, killing 21 and injuring 150.

The Purity Distilling Company built a large molasses storage tank on Commercial Street in Boston’s North End to store molasses until it could be distilled into alcohol. In early January 1919, just a few days before the disaster, a ship had discharged a full load of molasses into the tank. When the cargo was discharged, the weather was cold, only around 4 degrees F. Then on January 15th, the temperature rose suddenly to an unseasonably warm 40 degrees.

The molasses began to expand stressing the steel of the 54 high and 90-foot diameter tank. The tank groaned and wept molasses from the tank seams under the load. Then at around 12:30 in the afternoon, when the streets were occupied with workers from the distillery and local factories breaking for lunch, there was a sound like gunfire as the tank’s rivets popped and the steel plates ripped open. The tank collapsed, dumping 2,300,000 US gallons of molasses in a 25-foot high wall of molasses surging through the streets at a speed estimated to be 35 mph (56 km/h). Twenty-one died and 150 were injured.

As reported by Scientific American: The deluge crushed freight cars, tore Engine 31 firehouse from its foundation and, when it reached an elevated railway on Atlantic Avenue, nearly lifted a train right off the tracks. A chest-deep river of molasses stretched from the base of the tank about 90 meters into the streets. From there, it thinned out into a coating one half to one meter deep. People, horses, and dogs caught in the mess struggled to escape, only sinking further.

To understand why a wave of molasses could do so much damage requires some science. Scientific American explains: A wave of molasses does not behave like a wave of water. Molasses is a non-Newtonian fluid, which means that its viscosity depends on the forces applied to it, as measured by shear rate. Consider non-Newtonian fluids such as toothpaste, ketchup, and whipped cream. In a stationary bottle, these fluids are thick and goopy and do not shift much if you tilt the container this way and that. When you squeeze or smack the bottle, however, applying stress and increasing the shear rate, the fluids suddenly flow. Because of this physical property, a wave of molasses is even more devastating than a typical tsunami. In 1919 the dense wall of syrup surging from its collapsed tank initially moved fast enough to sweep people up and demolish buildings, only to settle into a more gelatinous state that kept people trapped.

First to the scene were 116 cadets under the command of Lieutenant Commander H. J. Copeland from USS Nantucket, a training ship of the Massachusetts Nautical School (which is now the Massachusetts Maritime Academy), that was docked nearby. They were soon joined by Boston Police, Red Cross, Army, and Navy personnel.

Cleanup crews used salt water from a fireboat to wash the molasses away and used sand to try to absorb it. The harbor was brown with molasses until summer. The foot traffic of rescue workers, cleanup crews, and rubberneckers, spread the sticky mess around the city on people’s shoes. In all, the cleanup effort required over 80,000 man-hours.

Local residents brought a class-action lawsuit against the United States Industrial Alcohol Company, the owner of Purity Distilling. The company blamed terrorists. Because some of the alcohol was used to make munitions, they said that the tank must have been blown up by Italian anarchists. The court-appointed auditor found that the tank had been shoddily built and awarded the victim’s families $628,000 in damages, or around $9 million in current terms.

Not as bad as the molasses spill.

Google “Chocolate Highway” for videos:

A river of chocolate flows on Arizona highway after traffic incident

(CNN)A tanker hauling 40,000 pounds of liquid chocolate (3,500 Gallons) rolled over on the interstate near Flagstaff, Arizona, on Monday, leaving a river of the sweet liquid all over the road.

https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/14/us/chocolate-spill-interstate-arizona-trnd/index.html

Who is lying here?

Arizona or Poland?

Look at the license plate numbers.

A tanker truck spilled tons of liquid chocolate on a Polish highway. Here’s what that looked like.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/food/wp/2018/05/09/a-tanker-truck-filled-with-tons-of-chocolate-spilled-on-a-polish-highway-heres-what-that-looked-like/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.3531c5656e17

Thanks for the article! : come listen to this song by Kites & Crows about the Great Molasses Flood. http://kitesandcrows.net/track/black-tide

There is an old jingle in England about the behaviour of ketchup.

‘ If at first you shake the bottle,

You’ll get a little, then a lottle.

The very interesting explanation of Newtonian fluids with this molasses article gives the jingle a real scientific basis. A lifetimes puzzle solved in one hit. Thanks!