Shad, often referred to as the “poor man’s Salmon,” once returned yearly to spawn in the Hudson River estuary from New York Harbor north to Fort Edward. Overfishing, habitat loss, and pollution contributed to a series of population collapses, and shad fishing on the Hudson River was closed in 2010. Now New York State wants to grow shad populations in the river until recreational catch-and-release is once again possible, with the eventual goal of reopening commercial fishing.

Shad, often referred to as the “poor man’s Salmon,” once returned yearly to spawn in the Hudson River estuary from New York Harbor north to Fort Edward. Overfishing, habitat loss, and pollution contributed to a series of population collapses, and shad fishing on the Hudson River was closed in 2010. Now New York State wants to grow shad populations in the river until recreational catch-and-release is once again possible, with the eventual goal of reopening commercial fishing.

Long before the first Europeans arrived at the Hudson River, Native Americans feasted on the schools of American shad that returned to the river to spawn in the Spring. They often smoked the flesh and consumed the roe. Early European settlers learned the importance of shad from the Natives and quickly picked up the technique of smoking them to provide food for the harsh winters when game was scarce.

Shad played an important role in the lives of both Benjamin Franklin and George Washington. In 1771, the soon-to-be “Father of our Country” caught nearly 8,000 of them as part of his commercial shad fishing operation. It was but one of young Washington’s many business enterprises, but one of his most profitable.

The New York Almanac notes that some historians believe that it was an unexpected early run of shad up the Schuylkill, a tributary of the Delaware, that saved Washington’s men from starvation while stationed at Valley Forge following the brutal winter of 1778. At least one account has the soldiers under the command of General John Sullivan—for whom Sullivan County is named—riding into the Schuylkill on horseback and thrashing about in the water to drive huge numbers of shad into crudely constructed nets. A feast of “the most savory fish” ensued.

The connection between Colonial America and the shad is so strong, in fact, that the prolific writer John McPhee, an avid fisherman himself, has not lightly dubbed the shad “The Founding Fish”. McPhee’s 2002 book of that title “illuminates the sometimes surprising relevance of [shad] in seventeenth and eighteenth century America.”

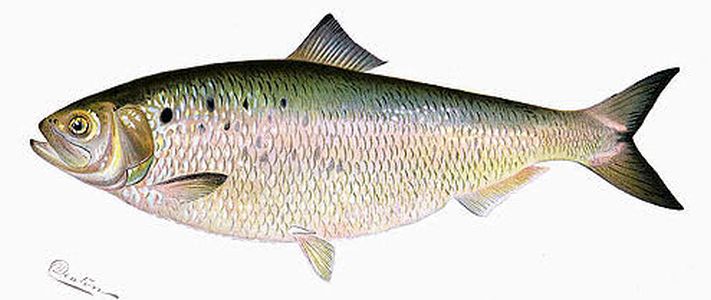

The silvery-blue fish, which can grow up to 30 inches, was an important food source in the region and was commercially fished on the Hudson in the 19th and 20th centuries, becoming essential during World War II as fishing trawlers were forced from the open Atlantic by the specter of Nazi U-boats.

The state Department of Environmental Conservation released a final report in late March laying out how this can be accomplished and setting benchmarks for when the fisheries can be reopened. The DEC sets out a nearer-term goal of returning shad populations to their levels in the mid-1980s, with an eventual goal of returning them to 1940s levels.

Shad populations were already significantly impacted by the 1940s — the first recorded population collapse happened in the mid-1800s — but the DEC sets this goal because dredging in the upper third of the estuary, which filled in many of the braided side channels where shad reproduced, was complete by this time, with the Hudson looking much like it does today.

Still, it may take years or decades for shad populations to recover to 1940s levels, according to the report.

Shad are anadromous, meaning they spend most of their lives at sea, returning to rivers to breed. Because of this, shad caught in the Hudson are safe to eat, since pollutants in the river are not present in shad to the degree that they are in fish that spend their entire lives in the river.

Meanwhile over here we will soon be eating shark – rock salmon:

https://www.ft.com/content/566c0d35-d148-4556-98ba-46fe063d6556

It will make a change from during WW II we ate conger eel steaks!